Clinical Diagnosis for MBBS: History, Examination, and Clinical Reasoning

Welcome to the most important focus in your MBBS curriculum.

And it’s not about learning medical subjects. It's about learning to think like a doctor.

To alleviate a patient’s suffering, a doctor must first identify the nature of the illness affecting the individual—in other words, establish an accurate diagnosis. How a doctor’s mind works from the first patient encounter to the provisional diagnoses.

By the end of the session, students should:

• Recognize that diagnosis is not a guess, but a structured reasoning process.

• Appreciate the ‘importance of history and examination’ before investigations.

• Understand the ‘sequence and logic’ of clinical diagnosis-making.

Introduction: “The Doctor as a Detective

What do a detective, a historian, and a doctor have in common?

They all solve mysteries by reconstructing a story from fragments of evidence.

A diagnosis is built ‘step by step’ based on FOUR main steps of collecting information

Step 1: The Clinical History — The Foundation: Every patient tells you their diagnosis — if you know how to listen attentively and ask logical questions. 80–85% of diagnoses can be made from the history alone.

Step 2: General Physical Examination (GPE):

This is where observation begins even before touching the patient. E.g. posture, body built, distress, pallor, icterus, cyanosis, clubbing, lymph nodes, edema, vital signs. GPE offers ‘global clues’

Examples

• Clubbing → suggests chronic hypoxia, chronic lung disease, cyanotic heart disease (systemic effect)

• Pallor → suggests anemia

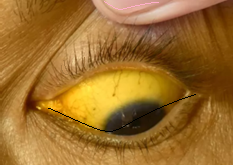

• Icterus → indicates hyperbilirubinemia, affecting the whole body

• Edema → may reflect cardiac, renal, or hepatic disease

• Cachexia → suggests chronic illness like TB, malignancy, or HIV

Step 3: Systemic Examination (SE):

Physical examination of the major systems: CVS, RS, GIT, GUT, CNS, and locomotor system.

Each system is examined in the following sequence:

• Inspection → Palpation → Percussion → Auscultation

Systemic examination is guided by the history, with the examiner looking for specific signs suggested by the presenting complaints and risk factors, for example, auscultating specifically for a systolic murmur in a patient with suspected severe anemia. The findings may refine or refute your provisional list formed after history.

• Example: A patient with cough — dull percussion, bronchial breath sounds → consolidation.

Connect each finding logically to the diagnosis-building process.

Step 4: Synthesis — Correlate and Conclude

After history and examination, pause and think aloud:

1. What are the possible causes (differential diagnoses)?

2. What finding best supports or contradicts each?

3. Which one fits the ‘entire clinical picture’?

Only then decide what investigations are truly needed — to confirm, not to discover.

“Differential diagnosis” means making a list of all possible diseases that could explain the patient’s symptoms, usually arranged from most to least likely.

This list is a key part of patient ‘management’ from the very first visit because it helps doctors think broadly and not miss serious but rare conditions.

Writing only an “impression” is too narrow, while a full differential diagnosis keeps all reasonable possibilities in mind so the treating team can investigate and treat appropriately.

Core Principle: In up to 80% of cases, the final diagnosis can be made or strongly suspected based on a thorough History and Physical Examination alone. Lab tests and imaging usually confirm the suspicion.

Plan of Management

A management plan is made after taking the history, performing the examination, and drawing up a list of differential diagnoses. This includes any special investigations in order to reach a final diagnosis.

The final diagnosis has to be built up after a logical analysis of symptoms, signs and selected investigations

Special clinical examinations and investigations will be discussed during your clinical rotations where you will present individual cases.

References:

• Glynn M, Drake WM. Hutchison's clinical methods: an integrated approach to clinical practice. 24th ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2017

• Douglas, G., Nicol, F., & Robertson, C. (Eds.). (2018). Macleod's clinical examination (14th ed.). Elsevier.

• Kundu AK. Bedside clinics in medicine. 9th ed. New Delhi: CBS Publishers & Distributors; 2024.

• Lloyd H, Craig S (2007) A guide to taking a patient’s history. Nursing Standard. 22, 13, 42-48

Watch Video for this blog: https://youtu.be/OBy9aOpJjNs

Watch HINDI video for this blog: https://youtu.be/myBaiam0aIM

4-Step Art of Diagnosis: What Medical School Can't Fully Teach: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/4-step-art-diagnosis-what-medical-school-cant-...

Introduction to history taking: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/introduction-history-taking-3rd-semester-students

Taking a Meaningful Clinical History: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/taking-meaningful-clinical-history

Format for Clinical History Taking: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/format-clinical-history-taking

History taking in a paediatric patient: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/history-taking-paediatric-patient

5-Page ANC History Taking Format: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/5-page-anc-history-taking-format-essential-gui...

Why ANC History Taking Matters?: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/why-anc-history-taking-matters

#Obstetric index (GPAL) in Antenatal Case History: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/obstetric-index-gpal-antenatal-case-history

#Decoding Gravida and Para: Terms in Antenatal History Taking: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/decoding-gravida-and-para-terms-antenatal-hist...

#Duration of Pregnancy: Understanding the Trimesters and Gestational Age Categories: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/duration-pregnancy-understanding-trimesters-an...

#Calculation of Expected Date of Delivery (EDD) and Period of Gestation (POG): https://ihatepsm.com/blog/calculation-expected-date-delivery-edd-and-per...

#Antenatal Care and Case Booking: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/antenatal-care-and-case-booking

#Clinical Significance of Antenatal History Components (Socio-Demographic components): https://ihatepsm.com/blog/clinical-significance-antenatal-history-compon...

Antenatal History Taking: Significance of Clinical Components: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/antenatal-history-taking-significance-clinical...

Trimester-wise History Taking in Antenatal Care: FIRST Trimester: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/trimester-wise-history-taking-antenatal-care-f...

Trimester-wise History Taking in Antenatal Care: SECOND Trimester: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/trimester-wise-history-taking-antenatal-care-s...

Trimester-wise History Taking in Antenatal Care: THIRD Trimester: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/trimester-wise-history-taking-antenatal-care-t...

Trimester-wise History Taking in Antenatal Care: A Comprehensive Guide (all 3 trimesters): https://ihatepsm.com/blog/trimester-wise-history-taking-antenatal-care-c...

Components of Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness (BPCR): https://ihatepsm.com/blog/components-birth-preparedness-and-complication...

BPCR in brief: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/%E2%80%98birth-preparedness-and-complication-r...

Specific Health Protection during Antenatal Visits: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/specific-health-protection-during-antenatal-vi...