The main purpose of the Clinical Rotations from third semester is to build your ability to function progressively as an independent but supervised clinician.

It is important to gain knowledge about human anatomy and physiology, pathology, microbiology and also the range of medical disorders. It is also necessary to learn to look for the signs and symptoms in actual patients. Hence you are taught both in parallel.

Hence for becoming a true doctor, the learning outside of the classroom through experiences with patients is an equally important part as is attending lectures and self-reading. So the substantial portion of your training has to be self-directed.

If History taking and physical examination is done sincerely, the information you collect on a patient will probably be more detailed than that obtained by duty doctors. It is not uncommon that a MBBS student detects a key finding that changes the management of the patient.

Hence, evaluate as many patients on your own as possible. If permissible, even before others get a chance.

History Taking

Clinical history is the most important component in evaluating a patient. It allows the patient to narrate their own account of the complaints and in their own words. This provides the most crucial information the doctor. It’s important to consider the patient’s beliefs and to remain non-judgmental. It’s essential that the doctor should not look hurried, otherwise the patient may hesitate in providing complete information and you may miss critical evidence.

Though we will discuss in detail about the components of history taking in another lecture, we need to build a picture here.

The first information is the demographic details followed by ‘Presenting complaint/s’ which is the problem for which the patient has reported to the clinic/hospital.

So ask ‘what brings you here’ or ‘tell me the problem’. It is an open-ended question. List the problems in:

• Patient’s own language

• Chronological order

Next is the ‘History of Presenting Complaints’:

Here, the chief complaints are discussed in more detail e.g. the mode of onset (acute/sub-acute/insidious), its progress (increasing/stable/off & on/absent currently/aggravating and relieving factors etc.). The treatment taken, its response to treatment and the course till the day of current interaction can give a lot of clues to the diagnosis.

Therefore, ask open-ended (indirect) questions in the beginning e.g. ‘tell me more about…..”, “What happened next….”, “what do you think…”. Once you start getting an idea of which phenomena may be at play, the questions automatically become close-ended (direct). These questions are aimed at checking the presence of tell-tale signs of the numerous phenomena that may be coming to your mind (there may be many at this point). This is often referred to as taking ‘negative history’. I personally don’t like calling it that because students make the mistake of creating a heading ‘Negative history’ and that may annoy certain examiners.

Remember:

• Do not ask direct questions early on as you may be suggesting a diagnosis to the patient who may go along and together you arrive at a wrong diagnosis.

o Do not ask leading questions for the same purpose.

• All along, ask questions in patient’s language and use no medical terms.

o Let the patient narrate the answers in their own language and record them like that.

o In fact, use the same language for presenting the history to examiner/seniors.

• Ultimately, it should flow like a story in a conversation.

• There is no place for your own interpretations or examination findings here.

Generally, the HOPC can be 30 – 50% of total history as it is detailed, chronological narrative including important negative responses.

When taken in this way, you already have a long list of probable diagnoses or at least the possible pathology at play or the possible system affected or the organ involved, depending upon your stage in the development of an experienced doctor.

As you explore each symptom in detail, some picture starts to form in your mind. So ask:

• Mode of Onset – was it sudden, or over a short time or has it developed over long time?

• Duration – how long does it last, minutes, days or weeks?

• Site and radiation – where in the body? Does it occur anywhere else too?

• Aggravating and relieving features – what makes it better or worse?

• Associated symptoms – when this happens, does anything else happen with it, such as nausea, vomiting or headache or anything else?

• Progress – Has it increased or decreased from time of onset, or has remained the same?

• Frequency – how many times a day/week/month/year etc.?

As the patient thinks and answers your questions in their own language, you can deduct some facts depending upon your current level of medical knowledge.

In general the headings under history taking are:

• The presenting complaint.

• History of Presenting complaint

• Past medical history.

• Medication history.

• Occupational history

• Personal history

• Dietary history

• Menstrual history

• Obstetric history

• Family history.

• Social history.

• Review of systems

• Additional heading in special cases

Making a list of possible diagnoses: the ‘differential diagnosis’

After completing the history, apply ‘deductive reasoning’ to identify the probable pathological process behind the patient’s illness.

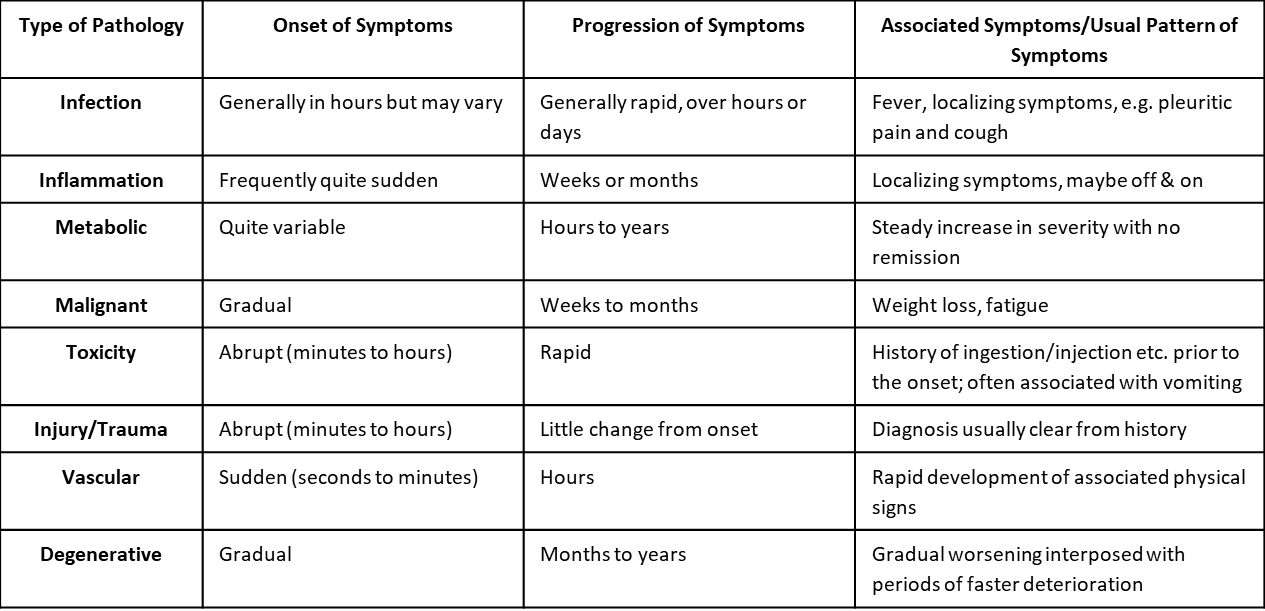

Begin by asking yourself, “What type of pathology could explain these symptoms?”

All diseases are broadly

• Congenital or

• Acquired

Acquired disorders result from a limited range of pathological mechanisms—such as

• Infection,

• Inflammation,

• Degeneration,

• Neoplasia

• Trauma

• Metabolic Dysfunction etc.

Details from the complaint’s

• Location

• Onset,

• Pattern,

• Rate of progression,

• Associated features etc.

Will narrow your focus toward one or more of the above-mentioned mechanisms.

Consider this reasoning process in an example:

A 65‑year‑old presented with:

• Cough: for last 2 months

‘Personal history’ reveals ‘moderate smoking’ for 15 years

Cough, his age and smoking raise the likelihood of some ‘disease’ in the lungs. What all can fit this picture?

1. Tuberculosis

2. Lung cancer

3. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Now, upon further enquiry he also reports ‘chest pain’,

• This does not rule out COPD—it could be a ‘muscle strain due to frequent intense coughing’.

• On the other hand, it may be a ‘pleuritic pain’ indicating ‘infection or pulmonary embolism’,

• The characteristics of these two types of pain differ and this seems more like pleuritic pain

This fact can add pleuritic pain to the list

1. Lung cancer

2. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

3. Tuberculosis

4. Pleuritic pain due to infection or embolism

During the review of systems, the patient reported having seen blood in sputum (haemoptysis) off and on for two months strengthens the suspicion of ‘lung malignancy’ or ‘tuberculosis’ and the coexistence of ‘weight loss’ further increases the probability of these diagnoses.

RANK the diagnoses in the list in order of probability: Consider the following

• The epidemiology of the disease

• Number of symptoms explained by it.

• Consider the common diagnosis first, only then the rare ones.

By logically connecting these clues, you refine your ‘differential diagnosis’,

Next: You can proceed to physical examination of the patient. You can look for specific signs which are commonly found in these diseases.

If none are found, you may go back to ask more history, looking for more suggested diagnosis.

• However remember to present the history all at once, while presenting the case

• Examination findings come only later, under the heading ‘clinical examination’ where no element of history should appear.

Summary

Rules of History Taking:

• Begin with open-ended questions and then narrow down to more specific questions as necessary.

• Also gather a complete social history and review of systems,

Rules while Presenting History:

Adhere rigidly to the format: PC, then HOPC, then past medical history (PMH), etc.

• Make the transition between each section clear and keep the sections separate.

Do not discuss physical exam (PE) findings in the history.

• PE should describe information you gather by looking at, listening to, or touching the patient.

• Do not put your conclusions or interpretation in the primary data section.

After both history and physical examination of the patient: Refining the Differential Diagnosis

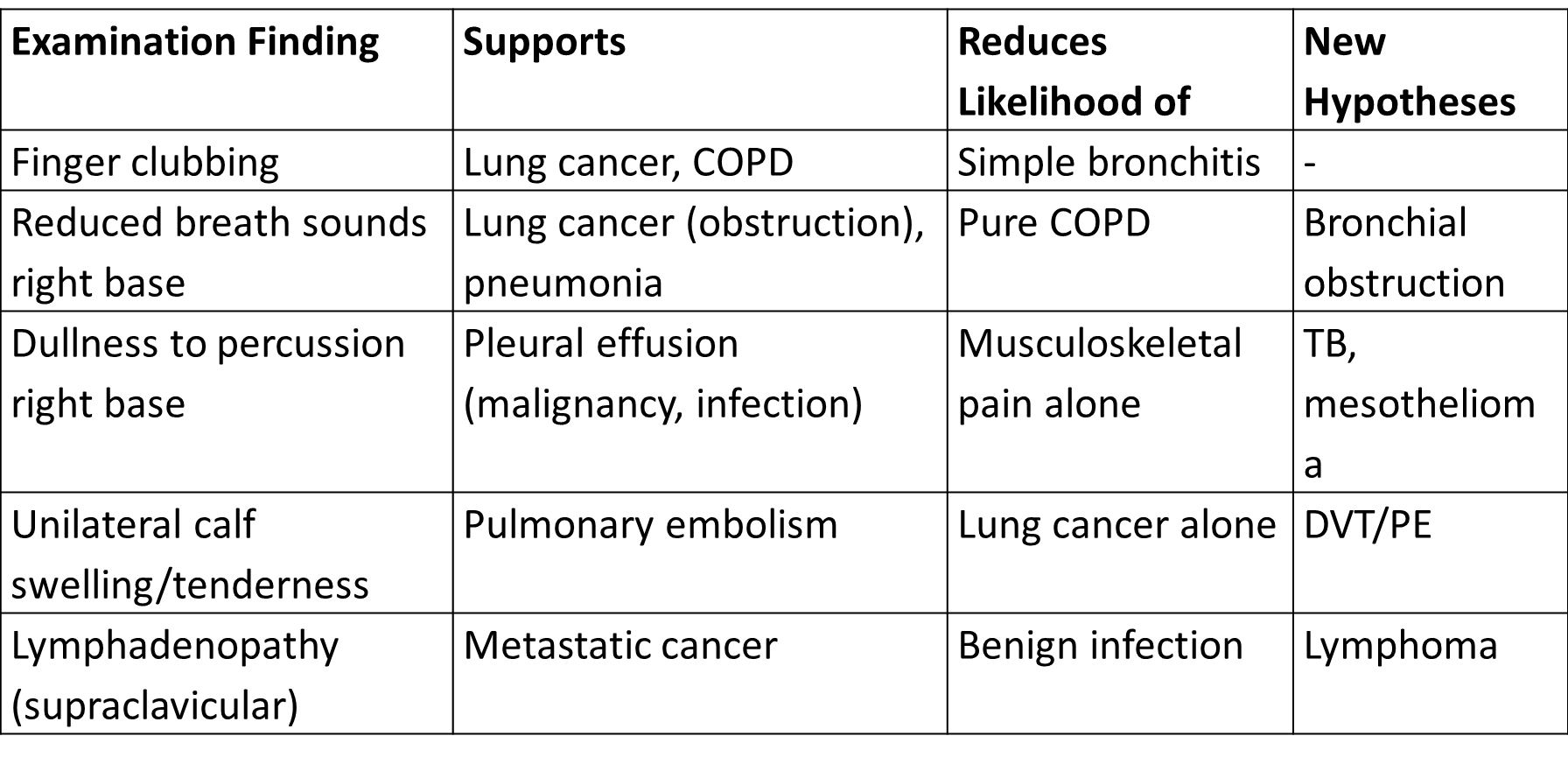

With your ‘initial differential diagnosis’ established from the history, proceed to the ‘physical examination’ to test each hypothesis systematically.

• Ask yourself, “Which findings would support or refute each possibility on my list?”

‘Deductive Process Post-Examination:’

- ‘Supportive findings’ elevate probability (e.g., clubbing strengthens lung cancer hypothesis)

- ‘Absent expected findings’ reduce likelihood (e.g., no lymphadenopathy lowers TB suspicion)

- ‘Unexpected findings’ may require adding new hypotheses (e.g., unilateral leg swelling suggests DVT)

‘Update Your Differential Using This Framework:’

1. ‘Rank by Probability:’ Reorder based on how well findings match each diagnosis

2. ‘Add/Remove Hypotheses:’ Incorporate new clues while eliminating unlikely ones

3. ‘Prioritize Life-Threatening Conditions:’ Focus investigations on highest-risk diagnosis first

‘Continuing the Example (65-year-old male smoker with 2-month cough, chest pain, hemoptysis, weight loss):’

Some examples of Examination Findings and Their Impact

‘Revised Differential Diagnosis After Examination:’

1. ‘Lung cancer’ (↑↑↑ probability: smoking + age + haemoptysis + weight loss + clubbing + focal signs)

2. ‘Pulmonary embolism’ (↑ probability: if leg swelling present)

3. ‘Pneumonia secondary to obstruction’ (↑ probability: focal signs)

4. ‘COPD exacerbation’ (↓ probability: focal findings atypical)

5. ‘TB’ (consider if effusion + weight loss)

Next Steps (Investigation Plan):

Now direct targeted tests to ‘confirm the leading diagnosis’ and ‘rule out life-threatening alternatives’: Skip the details for now

SYMPTOMS and SIGNS

A symptom is a subjective experience reported by the patient, such as pain, fatigue, or dizziness, which cannot be directly observed by others.

A sign is an objective indication of a disease that can be observed and measured by others, such as a physician or other healthcare provider.

Example: When presenting a case with "intermittent abdominal pain and weight loss," specify:

Presenting Complaints

• Recurrent abdominal pain X 3 months

• Weight loss X 2 months

• Symptoms: "Patient reports:

• Recurrent abdominal pain and

• Weight loss of 2 kg"

• Signs: "Examination revealed:

• Abdominal tenderness in epigastrium;

• Weight loss documented; 58 kg (down from 60 kg)"

References:

• Glynn M, Drake WM. Hutchison's clinical methods: an integrated approach to clinical practice. 24th ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2017

• Douglas, G., Nicol, F., & Robertson, C. (Eds.). (2018). Macleod's clinical examination (14th ed.). Elsevier.

• Kundu AK. Bedside clinics in medicine. 9th ed. New Delhi: CBS Publishers & Distributors; 2024.

• Lloyd H, Craig S (2007) A guide to taking a patient’s history. Nursing Standard. 22, 13, 42-48

4-Step Art of Diagnosis: What Medical School Can't Fully Teach: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/4-step-art-diagnosis-what-medical-school-cant-...

Introduction to history taking: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/introduction-history-taking-3rd-semester-students

Taking a Meaningful Clinical History: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/taking-meaningful-clinical-history

Format for Clinical History Taking: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/format-clinical-history-taking

History taking in a paediatric patient: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/history-taking-paediatric-patient

5-Page ANC History Taking Format: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/5-page-anc-history-taking-format-essential-gui...

Why ANC History Taking Matters?: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/why-anc-history-taking-matters

#Obstetric index (GPAL) in Antenatal Case History: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/obstetric-index-gpal-antenatal-case-history

#Decoding Gravida and Para: Terms in Antenatal History Taking: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/decoding-gravida-and-para-terms-antenatal-hist...

#Duration of Pregnancy: Understanding the Trimesters and Gestational Age Categories: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/duration-pregnancy-understanding-trimesters-an...

#Calculation of Expected Date of Delivery (EDD) and Period of Gestation (POG): https://ihatepsm.com/blog/calculation-expected-date-delivery-edd-and-per...

#Antenatal Care and Case Booking: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/antenatal-care-and-case-booking

#Clinical Significance of Antenatal History Components (Socio-Demographic components): https://ihatepsm.com/blog/clinical-significance-antenatal-history-compon...

Antenatal History Taking: Significance of Clinical Components: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/antenatal-history-taking-significance-clinical...

Trimester-wise History Taking in Antenatal Care: FIRST Trimester: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/trimester-wise-history-taking-antenatal-care-f...

Trimester-wise History Taking in Antenatal Care: SECOND Trimester: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/trimester-wise-history-taking-antenatal-care-s...

Trimester-wise History Taking in Antenatal Care: THIRD Trimester: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/trimester-wise-history-taking-antenatal-care-t...

Trimester-wise History Taking in Antenatal Care: A Comprehensive Guide (all 3 trimesters): https://ihatepsm.com/blog/trimester-wise-history-taking-antenatal-care-c...

Components of Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness (BPCR): https://ihatepsm.com/blog/components-birth-preparedness-and-complication...

BPCR in brief: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/%E2%80%98birth-preparedness-and-complication-r...

Specific Health Protection during Antenatal Visits: https://ihatepsm.com/blog/specific-health-protection-during-antenatal-vi...